Editor’s Note: This is part one of a two-part article.

It is becoming increasingly clear from neuroscience research that intelligence is not fixed and that the ability to learn, think and problem-solve can be enhanced at any age. The implications of this new knowledge in the workplace are profound. It means that poorly prepared entry-level workers can make significant improvements in their ability to meet workplace requirements, becoming retrained in weeks. It means that the effectiveness of corporate training programs can be dramatically improved, whether the training is for job-specific skills or so-called soft skills like critical thinking, communication, or collaboration. It means that it is possible to develop the overall cognitive capacity of both individuals and organizations.

The Role of Cognitive Capacity

Every year, employers spend over $100 billion on employee training and development. Employee training programs range from remedial reading and math to executive coaching and development and from job-specific skills to so-called soft skills, such as creativity and leadership.

Many employers bemoan the fact that too many workers are unprepared for the demands of today’s workplace. Because the amount of new technical information is doubling every two years, students starting a four-year technical or college degree today will find that half of what they learn in their first year of study will be outdated by their third year. Following that logic, much of what students learn by the time they earn their diploma and find a job will be obsolete and will need to be updated and relearned on the job. According to Cathy Davidson, co-director of the annual MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Competitions, 65% of today’s elementary school children may eventually work in jobs that haven’t yet been created.

That’s why the job of training a workforce is vastly different than it was just a few decades ago. As one leading researcher characterizes it, “Today’s central managerial challenge is to inspire and enable knowledge workers to solve, day-in and day-out, problems that cannot be anticipated.” And if most workers must be knowledge workers, they must be adept at acquiring knowledge. In other words, they must be learners. Whatever the specific skills workers need to acquire, each employee’s cognitive capacity to take in and process information, store, retrieve, and problem-solve with it, and continue learning determines his or her effectiveness. The evidence is becoming stronger every day that, as one group of researchers expressed it, “The modern workplace runs largely on the cognitive abilities of its workforce.”

The dramatic nature of the change over the last several decades is illustrated by a list of occupations typical of various IQ levels created in 1977:

IQ Level Typical Occupation

• 140 Top Civil Servants; Professors and Research Scientists

• 130 Physicians and Surgeons; Lawyers, Engineers (Civil and Mechanical)

• 120 School Teachers, Pharmacists; Accountants; Nurses; Stenographers; Managers

• 110 Foremen; Clerks; Telephone Operators; Salesmen; Policemen; Electricians

• 100+ Machine Operators; Shopkeepers; Butchers; Welders; Sheet Metal Workers

• 100- Warehousemen; Carpenters; Cooks/Bakers; Small Farmers; Truck/Van Drivers

• 90 Laborers; Gardeners; Upholsterers; Farmhands; Factory Packers and Sorters

Generally, one can observe that occupations typical of higher intelligence pay more than those typical of lower levels of intelligence. Interestingly, research indicates that occupations’ cognitive ability ratings explain about 60% of the variation in income across occupations. In other words, people with higher general cognitive capacity (or intelligence) will usually make more than those with lower general cognitive capacity.

Of critical importance is that, in 21st century America, the demand for machine operators, sheet metal workers and warehousemen is in decline. The jobs that remain require a higher level of cognitive functioning and comfort with technology. What happens in our workplaces when the demand for workers at higher IQ levels increases while the number of jobs suitable for lower IQ levels declines?

Fortunately, there is growing evidence that intelligence can be developed not just for remediation but improving fluid intelligence, the kind of intelligence required for problem-solving and thinking creatively and flexibly.

In the 1970s, Arthur Whimbey documented various interventions that enhanced the cognitive functioning of preschool children, which helped poorly performing college students take a more organized and effective approach to their academic work, and that improved individual performance on IQ tests.

More recently, the National Academy of Sciences published research suggesting that cognitive skills training can significantly increase human intelligence. As one of the researchers explained, “The key part of this work is the demonstration that it is possible to improve fluid intelligence, the type of intelligence that measures how people adapt to new situations and solve problems they’ve never seen before.

In a multi-site, controlled study, other researchers evaluated three different methods of improving fluid intelligence skills: 1) a memory training program, 2) an inductive reasoning skills program, and 3) a computer-based program to train processing speed – all three groups who went through an initial five-week intervention improved and retained a significant percentage of the improvement when tested five years later. The most pronounced results were experienced by the group who used the computer program. Of greatest importance, the enhanced cognitive skills developed by the subjects in the study transferred to everyday tasks, such as finding an item on a crowded pantry shelf, reading medication bottles, and reacting to road signs. Comprehensive, integrated cognitive skills training is being shown to have a significant impact on cognitive capacity, performance in basic skills, the effectiveness of job-specific-skills training, and the development of executive functions required for both hard and soft skills, including leadership.

Cognitive Skills: The Brain’s Infrastructure for Learning

Most of us take for granted the cognitive processes that enable us to learn because most of those processes happen at a non-conscious level. The graphic below illustrates how processes such as various attention skills, visual and auditory processing skills, processing speed, and other basic cognitive functions provide a foundation for higher-order cognitive processes and learning. Following are examples of cognitive processes that enable information to get into our brains from the outside world.

On top of those foundational cognitive skills are a set of cognitive skills referred to as core executive functions. These are the directive capacities of our brains and include:

Working memory: our ability to hold information in our mind while we manipulate it.

Inhibitory control: our ability to not do something we would otherwise do, including over the long-term (defer gratification).

Cognitive flexibility: our ability to change our mindset when the rules of the world around us change

The next tier of skills contains higher-order executive functions, like reasoning, problem-solving, and planning (among others), and Inhibitory Control, the ability to suppress a thought or idea and to refrain from doing something one otherwise would do.

All this infrastructure of cognitive processing is necessary to learn to read, learn to do math, and learn everything else that depends on reading and math. It is part and parcel of the applied skills or soft skills that managers refer to as being so necessary in today’s workplace. It is often taken for granted in training workers, in the same way, that it is taken for granted in school. But if the modern workplace runs largely on the cognitive abilities of its workforce, then the role of these skills and the ability to develop them must be reexamined and intentionally developed.

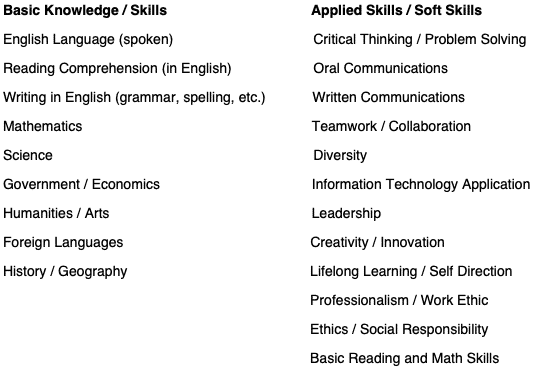

Skills Needed in the Workplace (from the Workforce Readiness Report Card)

According to the Workforce Readiness Report, there is a significant gap between the level, and types of skills employers seek in entry-level workers and the level of proficiency demonstrated by recent high-school graduates, including basic reading and math skills.

Moreover, the gap between workplace requirements and workforce readiness is widening. In 2003, 87% of adults tested below the proficient level in prose literacy, and even the average score of adults with graduate study was in the Intermediate-range (the level below Proficient). Between 1992 and 2003, the average scores for all education levels decreased in one or more literacy measures.

Level of Educational Attainment Change Between 1992 and 2003

• Less than or some high school – Down 9 points in prose literacy

• High school graduate – Down 6 points in prose literacy

• College graduate – Down 11 points in prose literacy &14 points in document literacy

• Graduate studies/degree – Down 13 points in prose literacy & 17 points in document literacy

Other studies have also identified significant gaps in the skills required for today’s jobs, estimating that between 25 percent and 40 percent of the current workforce lacks the basic skills to understand written or verbal communications. This workforce illiteracy costs U.S. businesses an estimated $225 billion a year in lost productivity.

When elementary and undergraduate education fails to prepare workers adequately, it falls to employers to provide remedial training. However, employers face many of the same challenges that schools and colleges face in re-mediating basic skills, including a broad diversity of backgrounds, learning styles, intellect, and culture among their workers. Organizations that use the same techniques and approaches used by the school systems that failed to prepare graduates for the workplace are likely to get the same result.

Recent research has begun to illuminate the importance of underlying cognitive skills in acquiring what many have previously considered basic reading and math skills. Researchers are showing that brain (cognitive skill) development can impact school achievement, emphasizing neurocognitive systems such as cognitive control, memory, and learning. Other researchers focus on the importance of cognitive processes such as planning, attention, simultaneous and successive processing.

As a result of these and other research efforts, educational and developmental psychology researchers have started to see the need to add training of basic foundational cognitive skills to the education system to foster basic skills acquisition. In fact, such interventions have been very successful in dramatically improving cognitive skills and reading and math levels for students with learning disabilities, students from low SES, and students behind grade-level and the general population. Gains from four to six years of cognitive ability and one to two years in the level of academic performance have been shown in 12 weeks.

- edCircuit – 3 Keys to Building Individual Learning Capacity

- Psychiatric Times – Move Over Data, Brain Capital is the New Oil