Crossing the Chasm in Education

The education market is crossing into the digital reality that other markets, like manufacturing, insurance, and retail, have already crossed. Typically, individuals make millions of small efforts to gain sufficient momentum to carry an initiative or company, or in this case, a whole market like education, out of the wading pool of novelty start-ups into the big leagues. With the dramatic influx of tablet computers in the last several years, loads of educators nationwide started this journey, carrying the sector into a digital transition.

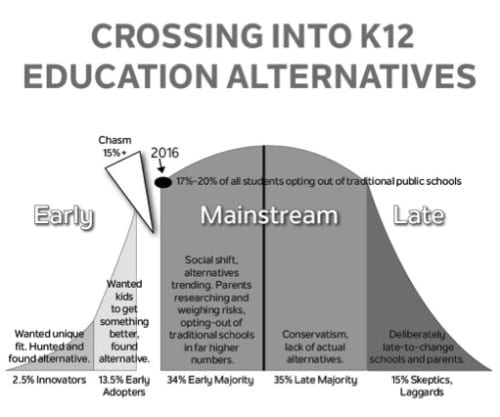

Interestingly, once a market reaches a certain amount of momentum, typically at around a 15 percent adoption, widespread change can happen. It starts to be noticeable, with more “buzz.” It’s a sort of magic point.

The 1991 book Crossing the Chasm by Geoffrey A. Moore argued that there is a gap that exists between the early adopters of any technology and the mass market because, typically, the groups are more conservative. He explained that many technologies initially get pulled into the market by enthusiasts but later fail to gain wider adoption because of this inherent market inertia. Institutions and markets tend to hold their form resolutely, decrying change in service to what they know or have known of structure. It has worked.

The education sector is famous for having many enthusiastic “one-offs,” or teachers who stand out from the rest in their tech and app use. School administrators often wonder how they can get “everybody else,” meaning all the other teachers in their school, to be the same.

The education sector is famous for having many enthusiastic “one-offs,” or teachers who stand out from the rest in their tech and app use. School administrators often wonder how they can get “everybody else,” meaning all the other teachers in their school, to be the same.

Getting uniform adoption and competency by users is the bane of all technology adoption in every sector. There is not just a chasm to cross for markets but for individuals. Some cross it more quickly than others, and some run to it, while others hold the form of their structure, primarily if it has worked for them in the past.

The “chasm” is typified by a bell curve showing that after technology enters the scene, about 2 percent are the early “Innovators.” Culturally, we have been known to call these the “lunatic fringe” when discussing politics or social anomalies. In education, they are a more interestingly rare type – those who find, figure out and alter their teaching practice to give their students something entirely different than what was done before. They are minor miracle workers and those that buck the norm.

The next group is the “Early Adopters.” These constitute another 13 percent plus the original 2 percent for 15 percent. In education, these teachers are willful about their teaching and may not be the first to try new tech, but they are always on the prowl for things that improve learning.

As soon as someone else legitimizes it, they are behind it, and soon. What’s interesting is that in the U.S. today, we have exceeded the 15 percent norm for alternative educational paradigms already. The chasm is between this 15 percent and the “Early Majority,” or the next 34 percent leading up to the top of the bell curve. This “Mainstream” group is the hard part. This is where we work to get every other teacher to remain fully digital and have new levels of administrative change to facilitate a difference across the board. It requires a determination by leaders to lead through change, to gain, themselves, the mindset of the “Innovators” at the beginning of the curve where running entirely on technology has never been done before. It’s a changed viewpoint.

We are likely in the stage of “crossing the chasm” as a society with education into a new digital reality. This is because once the early adopters and the early majority begin to transition to new technology or adopt change, a certain momentum creates inevitable for every other part of the market.

We are likely in the stage of “crossing the chasm” as a society with education into a new digital reality. This is because once the early adopters and the early majority begin to transition to new technology or adopt change, a certain momentum creates inevitable for every other part of the market.

There is a potential that learning consumerization is the bridge across the chasm for education to a place where the majority has adopted alternatives to traditional institutional public schooling.

In the U.S., we are already at the critical tipping point of children in the K-12 Education sector in various flavors of alternatives to traditional public education. The options to the historically typical school in the public system reached 17 percent in 2012, according to the data sets of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES 2013 study) depicting which types of schooling environments have what numbers of the total student body in K12. Granted, a large part of this was still public, just moved over into charter schools or “School Choice.”

What’s remarkable is that when this data is updated through 2016, it will probably show a much higher percentage have moved to alternatives since the charter schools and unschooling movement are stating record growth numbers.

Based on that data, the alternative shift is at least 20 percent, and indications are that it will continue to be pushed politically. These are also indicators that the technically sophisticated among us have allied with the monied interests to take advantage of the potential of digital learning, particularly items with consumer-like distributions.

Based on that data, the alternative shift is at least 20 percent, and indications are that it will continue to be pushed politically. These are also indicators that the technically sophisticated among us have allied with the monied interests to take advantage of the potential of digital learning, particularly items with consumer-like distributions.

This means learning consumerization has more than a slight chance of structural significance in the future of learning distribution. The change will not be like a tsunami, despite these numbers indicating a fast-moving crossing for this last great market, education.

Tools for sharing information, working systems, new best practices, digital lessons, and complete district-wide digital curriculum inventories (and making them accessible to all instructors) will become critical.

Schools still have time. Building high-value digital curriculum software is not as simple as an animated game. Rigid materials packaged together into flawless experiential learning take much money and time. We will see a gradual evolution as more like the fast-moving and wide Gulfstream – teaming with life and possibility.

- Education Week – 3 Shifts in the Use of Ed Tech: Exploring, Personalizing, Closing Equity Gaps

- EMS1 – EMS education technology: 7 questions to answer before buying

- Education Week – Research-Based Tech Implementation: Q&A With Eric Sheninger and Tom Murray