How to challenge your students with their thinking by Todd Stanley

I have had a lot of conversations in my career where it is offered that the solution to the problem of challenging students is simply to add more rigor. It is as though a teacher could go to the spice rank and hunt amongst the dill and the Cayenne pepper to find a bottle of rigor that can simply be shaken on the class and the problem will be solved.

I have had a lot of conversations in my career where it is offered that the solution to the problem of challenging students is simply to add more rigor. It is as though a teacher could go to the spice rank and hunt amongst the dill and the Cayenne pepper to find a bottle of rigor that can simply be shaken on the class and the problem will be solved.

The major problem of simply adding rigor to the classroom is that there are a fair share of teachers who do not know what rigor actually is. They equate rigor with being harder. And how do you make the class harder? The easiest way is by giving students more things to do and less time to do them. This, my friend, is not rigor. In fact, many students resent just being given more, especially if it is the same work. The idea of rigor is to provide different work that is going to challenge students. And where is the best place to challenge a student? With their thinking.

This narrative follows into the assessment of students. How do you have rigorous assessments? By asking harder questions. But again, this is not rigor. You could ask a student to provide the name of the US Ambassador to China. It is not common knowledge that this would be Terry Branstad, but it is still just knowledge. There lies the problem. Just like giving more of the same work, asking questions that are all knowledge-based questions are not going to challenge students’ thinking no matter how difficult the question is.

To provide an example of different types of thinking, a teacher could ask this question: “What is your favorite book and why?” Students will not have to struggle to figure out what book is their favorite. They may have to think a little harder to determine the why of their choice. A lot of times students know they like something, they just cannot point to what exactly they liked about it. By having them break it down and analyze what elements of the book they enjoyed will access a higher level of thinking.

To provide an example of different types of thinking, a teacher could ask this question: “What is your favorite book and why?” Students will not have to struggle to figure out what book is their favorite. They may have to think a little harder to determine the why of their choice. A lot of times students know they like something, they just cannot point to what exactly they liked about it. By having them break it down and analyze what elements of the book they enjoyed will access a higher level of thinking.

Some would argue such a question is not hard. Some students could talk at length about their favorite book and why they love it so much. It is not a stretch for them to share their opinion. But this is definitely rigorous. Why is it rigorous? Because the level of thinking you are asking students to access is much higher.

It all comes down to Bloom’s Taxonomy. Bloom divided the types of thinking students do into six levels.

Many classrooms sit firmly ensconced in the apply, understand, and remember section of the taxonomy. This means that a majority of the time students are accessing the lower levels of their thinking in order to complete the task being asked of them. This does not mean what they are doing is not hard, what it does mean is it probably is not rigorous.

In order to be rigorous, students need to be in the top half of Bloom’s chart. They need to either be analyzing, evaluating, or creating in order to access their high levels of thinking. The question becomes, how much of this is being done in the classroom? Not just your projects or performance assessments. How much higher level thinking is being asked of students on a pencil to paper test? How much of it is being done in the questions teachers ask? How much of it is being displayed in the daily work students produce to show mastery?

Does this mean every activity or lesson should be higher level thinking only? No, the lower levels of thinking have their place in the classroom. These act as the building blocks to higher thinking. Without this basic knowledge, it would be difficult to think critically because you would not have the background knowledge needed to do so. The problem comes in that many teachers stop at this lower level rather than pushing students into the higher ones.

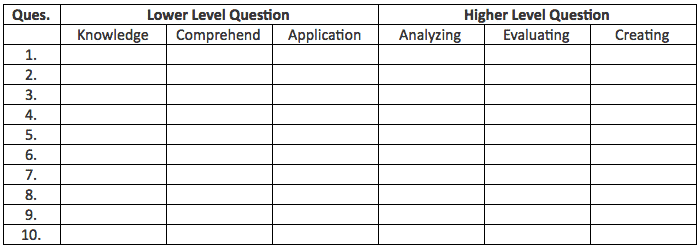

The ratio of high to lower level thinking students are doing in class should be about 50/50. That means half of the thinking being required of students is at the analyzing, evaluation, or creating levels. How does a teacher determine whether they are achieving this ratio or not? Look at your artifacts. Artifacts are anything you give to students whether it be a worksheet, an assessment, or a homework assignment. Analyze these artifacts to determine your ratio of lower to higher level thinking. You can use a sheet such as this:

For each question indicate the level of the question according to Bloom’s taxonomy.

Total the results at the bottom of the chart.

If you are placing all of your checks in the lower level sections, you need to ask yourself does this indicate that your class lacks rigor? If through this self-reflection you think this does indicate a lack of rigor, you might need to revise and edit the work you ask your students to complete.

You also might reflect upon the type of oral questioning you are asking students. If most of the questions you ask of your class have a definitive correct answer, you are probably asking too many lower level questions. If, however, students have several different ways they could answer the question, they are having to think critically and thus are being asked higher level questions.

This fundamental change in your classroom of reflecting on the level of thinking your work requires of students can immediately increase the rigor of your classroom. Some teachers might balk at this prospect because it is too hard. Keep in mind, raising the rigor in your classroom means raising the rigor on your teaching, but just like your students will be better learners, you will be a better teacher.

This fundamental change in your classroom of reflecting on the level of thinking your work requires of students can immediately increase the rigor of your classroom. Some teachers might balk at this prospect because it is too hard. Keep in mind, raising the rigor in your classroom means raising the rigor on your teaching, but just like your students will be better learners, you will be a better teacher.

Further Reading

- Teach Hub – 22 Ways to Add Rigor to Your Classroom

- TeachThought – How To Add Rigor To Anything

- The Art Of Ed – How to Develop Rigor in the Classroom