Table of Contents

edCircuit Opinion:

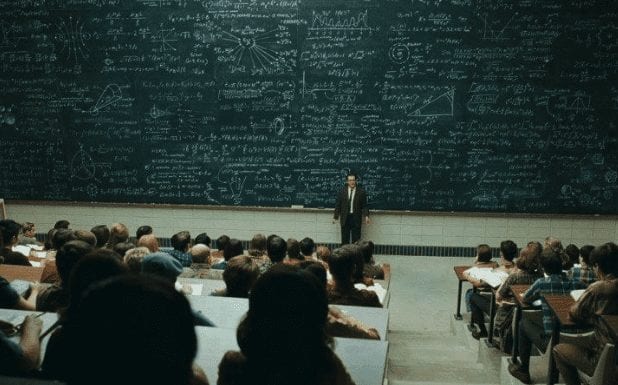

To many, the thought of lecturing in front of a large group of people is incredibly daunting. For educators, this is their everyday reality. It’s easy to assume that skilled public speakers are naturally talented and that effective communications are a rare group of outspoken and articulate individuals. The reality is that one’s ability to present in an engaging and persuasive way must be learned and frequently practiced. Without this skill, it’s easy to lose your audience’s attention.

The Atlantic published that many college lectures today are deemed as dull. Research has shown that students tune out after only 15 minutes of a lecture. With the average college class lasting approximately 80 minutes, there are 65 minutes of unproductive teaching. Professors are often not being taught how to present in a new and interesting way. Have you ever witnessed a presenter read directly from their notes? That’s what we are trying to prevent. Do you feel that traditional lectures should be eliminated? If not, what are ways that teachers can re-engage students and prevent the elimination of lectures?

At a Glance

- Research shows that in a lecture, students “tune out” after 15 minutes

- A growing body of evidence shows that mental imagery can accelerate learning and improve the performance of all sorts of skills.

Around the Web:

Should Colleges Really Eliminate the College Lecture?

Christine Gross-Loh | The Atlantic

As a doctoral candidate interviewing at a liberal-arts college some years ago, I rambled, waded through pages of notes, and completely lost my train of thought at one point during my job presentation. Even though I was eventually offered the position, I was keenly aware that, despite interviewing for a job in which I’d have to stand in front of students day after day, I’d never been trained in giving a lecture—and it showed.

But that lack of training is not unusual; it’s the norm. Despite the increased emphasis in recent years on improving professors’ teaching skills, such training often focuses on incorporating technology or flipping the classroom, rather than on how to give a traditional college lecture. It’s also in part why the lecture—a mainstay of any introductory undergraduate course—is endangered.

For some years now, students in MIT’s introductory physics classes, for example, have had no lectures, and physics departments at institutions around the country have been following suit. But while the movement to eliminate the college lecture first gained traction among physics professors, including the Stanford Nobel laureate Carl Wieman and Harvard’s Eric Mazur (a proponent of “peer instruction” who has compared watching a lecturer in learning physics to watching a marathon on TV to learn how to run), it has expanded beyond the sciences. Getting rid of the college lecture entirely is the mission of a broad group of educators.

To read more visit The Atlantic

If you can’t imagine things, how can you learn?

Mo Costandi | The Guardian

Never underestimate the power of visualisation. It may sound like a self-help mantra, but a growing body of evidence shows that mental imagery can accelerate learning and improve the performance of all sorts of skills. For athletes and musicians, “going through the motions,” or mentally rehearsing the movements in the mind, is just as effective as physical training, and motor imagery can also help stroke patients regain function of their paralysed limbs.

For most of us, visual imagery is essential for memory, daydreaming, and imagination. But some people apparently lack a mind’s eye altogether, and find it impossible to conjure up such visual images – and their inability to do so may affect their ability to learn and their educational performance.

Firefox co-creator Blake Ross recently described how it feels to be blind in your mind, and his surprise at the revelation that other people can visualise things. “I can’t ‘see’ my father’s face or a bouncing blue ball, my childhood bedroom or the run I went on ten minutes ago,” he wrote on Facebook. “I thought ‘counting sheep’ was a metaphor. I’m 30 years old, and I never knew a human could do any of this. And it is blowing my goddamned mind.”

To read more visit The Guardian