Questioning

Our questioning strategies reflect our high expectations. When we ask students higher order questions, we are showing them; we expect them to answer at higher levels. On the other hand, when we only ask students to recall questions such as, “Who did this”? We are demonstrating that we don’t really expect them to know any more than the most basic answers.

Questioning Mistakes

Questioning is a basic and critical part of your classroom. But we often make mistakes during our questioning. These include not probing beyond a single answer, not encouraging students to ask questions, and asking lower-level questions. On the student side, too often, one or two students dominate the conversation. In order to avoid some of these mistakes, let’s look at 3 keys to effective questioning.

Ask Questions that Match Your Purpose

The first key to effective questioning is to match your questions to your purpose. For example, if you want basic information from students, closed-ended questions, or those that ask for a one-word answer, are appropriate. However, if you want students to show a deeper level of understanding, open-ended questioning is preferred.

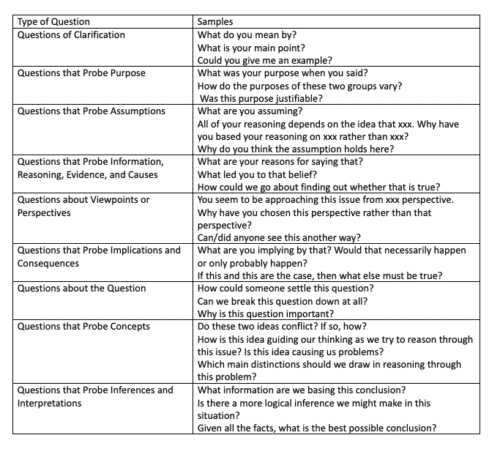

When I was teaching, I learned about the Paideia Seminar. A critical part of the seminar discussions was the notion of Socratic Questioning. Although some questions were provided for guidance, I still struggled with asking questions at the highest levels. In 2006, Richard Paul

Probe for More Depth

Probe for More Depth

One of the challenges related to questioning is that students may provide a surface level response rather than a complete answer to your query. In those cases, we need to ask additional questions to probe for more information. Probing allows you to gather more details in the case of an insufficient answer or when a student is reluctant to respond. In order to elicit more details, you’ll want to use prompts similar to these.

Over time, you can also teach students to ask probing questions of each other. Simply provide the sample prompts or others appropriate to your students, and guide them toward the peer questioning.

Ensure Participation by All Students

Finally, it’s important to ensure that all students participate in a discussion. Too often, we ask a question, and one student responds. Even if we ask, “Does everyone agree?” the other students simply nod, so they are not asked the question. In this case, only one student is truly involved in the questioning process.

As we plan our instruction, we should incorporate opportunities for each student to respond throughout the lesson. One of the simplest ways to ensure participation by all students is to use a pair-share, in which students share a response with a partner before a whole group discussion. I like to modify the traditional pair-share a bit to increase the level of rigor by asking students to share their partner’s answer rather than their own during the whole group discussion.

Asking students to use hand motions to respond can also be helpful. For example, students can show a thumbs up or thumbs down to provide yes/no feedback. Or, you can ask them to hold up between 1 and 5 fingers as to how well they understand the content. I also like to use a hand thermometer, where they rank the importance of a topic or once again show how well they understand a concept.

Finally, there are electronic options for student responses such as PollEverywhere, Kahoot, Plickers, Socrative, and Verso. I’ve also talked with teachers who use Twitter or simple text messaging to allow students to immediately provide information to teachers.

A Final Note

Questioning is a critical part of our instruction, but we must ensure that our questions match our purpose, allow for probing for more depth, and involve all students in the process.

- edCircuit –

- The Chronicle of Higher Education – How to Hold a Better Class Discussion

- Ed Week – How Much Should Teachers Talk in the Classroom? Much Less, Some Say