Table of Contents

The main question I hear from teachers is “What exactly is rigor? How do I know if our classrooms are rigorous?” In Rigor is NOT a Four-Letter Word, I defined rigor as “creating an environment in which each student is expected to learn at high levels, each student is supported so he or she can learn at high levels, and each student demonstrates learning at high levels” (Blackburn, 2013). Let’s look at this definition more closely, then turn our attention to differentiation.

“Making sure each student is learning at a high level in a Differentiated Classroom is key”

High Expectations

First, rigor expects each student to learn at high levels. Having high expectations starts with the decision that every student possesses the potential to be his or her best, no matter what.

Almost everyone I talk with says, “I have high expectations for our students.” Sometimes that is evidenced by the behaviors in the school; at other times actions don’t match the words.

Higher-level questioning is an integral part of a rigorous classroom. Look for open-ended questions, ones that are at the higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (analysis, synthesis).

Higher-level questioning is an integral part of a rigorous classroom. Look for open-ended questions, ones that are at the higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (analysis, synthesis).

It is also important to look at how I respond to student questions. It is common for teachers who ask higher-level questions to accept low-level responses from students. In rigorous classrooms teachers push students to respond at high levels. They ask extending questions. If a student does not know the answer, the teacher continues to probe and guide the student to an appropriate answer, rather than moving on to the next student.

Supporting Students to Learn at High Levels

High expectations are important, but the most rigorous schools assure that each student is supported so he or she can learn at high levels, the second part of our definition. It is essential that teachers design lessons that move students to more challenging work while simultaneously providing ongoing scaffolding to support students learning as they reach those higher levels.

Providing additional scaffolding throughout lessons is one of the most important ways to support students. This can occur in a variety of ways, but it requires that teachers ask themselves during every step of their lesson, “What extra support might my students need?”

Ensuring Students Demonstrate Learning at High Levels

The third component of a rigorous classroom provides each student with opportunities to demonstrate learning at high levels. I often hear that, “If teachers provide more challenging lessons that include extra support, then learning will happen.” I’ve learned that if I want students to show us they understand what they learned at a high level, I also need to provide opportunities for students to demonstrate they have truly mastered that learning. It’s important to use a common standard for rigor so that everyone has the same expectations. I use Webb’s Depth of Knowledge because of its focus on depth and complexity. As a caution, DOK is more than just verbs. If you search online and find a “verb wheel”, note that it was not developed by Dr. Webb and he does not endorse it.

The third component of a rigorous classroom provides each student with opportunities to demonstrate learning at high levels. I often hear that, “If teachers provide more challenging lessons that include extra support, then learning will happen.” I’ve learned that if I want students to show us they understand what they learned at a high level, I also need to provide opportunities for students to demonstrate they have truly mastered that learning. It’s important to use a common standard for rigor so that everyone has the same expectations. I use Webb’s Depth of Knowledge because of its focus on depth and complexity. As a caution, DOK is more than just verbs. If you search online and find a “verb wheel”, note that it was not developed by Dr. Webb and he does not endorse it.

Rigor and Differentiation

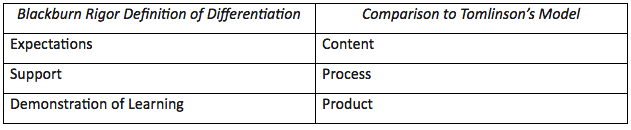

Many teachers have incorporated Differentiated Instruction in their classrooms. Developed by Carol Ann Tomlinson, the approach recommends that instruction be adjusted for small groups of students based on their readiness, interest or learning profile. Based on those criteria, teachers should adapt their content (curriculum), process (instruction), or product (assessment) in order to meet those needs. Notice how those adaptations match with our definition of rigor.

Differentiated Instruction provides customized instruction for different levels of students. However, a common criticism of Differentiated Instruction is that, by adjusting instruction for struggling students, teachers lower the level of rigor. By overlaying our definition of rigor onto the model, we can ensure rigor for all students.

For example, we might choose to adjust the content for struggling students. Perhaps we are teaching a lesson on Martin Luther King, Jr. and we choose a different, easier text for struggling students. We can ensure rigor and high expectations by incorporating higher order questions, albeit on lower content, or by asking students to read grade level text after they read the easier text. By reading the easier text first, they are able to move back to the grade level text with your support, because they have built prior knowledge and vocabulary skills (a strategy called Layering Meaning).

Or, we might adjust our process, or support. Let’s say we are teaching how to solve math word problems. We can adjust our support by providing a graphic organizer to struggling students. Not all students need this structure, so we accommodate those who do need support with an additional instructional strategy.

Finally, we might differentiate how students demonstrate their learning, or the product they complete. Perhaps I want students to analyze a series of events in a social studies lesson. A portion of my students are able to write a detailed analysis of the impact of those events on today’s society. Others may understand the material, but are unable to write an analysis paper. In those situations, it’s easy just to ask them to summarize the material, which is lowering the rigor. Instead, we could provide an opportunity for those students to verbally complete the analysis, perhaps by creating a video. In this case, struggling students demonstrate their learning at a rigorous level, just in a different way.

Finally, we might differentiate how students demonstrate their learning, or the product they complete. Perhaps I want students to analyze a series of events in a social studies lesson. A portion of my students are able to write a detailed analysis of the impact of those events on today’s society. Others may understand the material, but are unable to write an analysis paper. In those situations, it’s easy just to ask them to summarize the material, which is lowering the rigor. Instead, we could provide an opportunity for those students to verbally complete the analysis, perhaps by creating a video. In this case, struggling students demonstrate their learning at a rigorous level, just in a different way.

A Final Note

Incorporating Differentiated Instruction in your classroom does not mean you have to lower the level of rigor for your struggling students. However, we must be intentional about how we adjust our expectations, support, and demonstration of learning options so that we include rigor. Books are available at https://www.routledge.com/collections/10881. Check out my new book: Rigor and Assessment in the Classroom

- EdSurge – Is Homework Compatible With Personalized Learning?

- Education Week – Differentiated Instruction: A Primer

Subscribe to edCircuit to stay up to date on all of our shows, podcasts, news, and thought leadership articles.