Table of Contents

Continuing our series on adult SEL, Over the next two months, we’ll address self-awareness. Self-awareness is a skill most of us think we’ve developed. Examining that potentially misguided belief allows us to engage in a bit more self-awareness and fits nicely inside an attempt to better balance educators’ job demands and resources.

The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.”

When Verbal Kint shared his observation with Agent Kujan in the 1995 film “The Usual Suspects,” the line immediately worked its way into pop culture. In fact, Verbal’s musing borrows from centuries-old religious textual analysis. Going back to at least 1836, it is possible to find references to this notion of the devil’s overwhelming power, a great power that could conceal its very existence.

Regardless of one’s religious beliefs, we assume most readers will accept that, as humans, we’re capable of telling ourselves the truth and engaging in some self-deception. We can appeal to our better angels as well as bedevil ourselves. It takes a touch of self-awareness just to entertain the suggestion that, like the devil in the quote, we can convince ourselves of something untrue. So, to avoid fooling ourselves here, how might we understand what it means to be self-aware?

Defining Self-Awareness in Adult SEL

CASEL.org, one of the most commonly used social emotional learning frameworks in the nation’s schools, defines self-awareness competency as “the abilities to understand one’s own emotions, thoughts, and values and how they influence behavior across contexts. This includes capacities to recognize one’s strengths and limitations with a well-grounded sense of confidence and purpose.”

CASEL’s definition suggests a more introspective bent to self-awareness, but it is also important to include an outward-facing aspect to the definition of self-awareness. CASEL actually does this by naming another competency, Social-Awareness. They define that as “the abilities to understand the perspectives of and empathize with others, including those from diverse backgrounds, cultures, and contexts. This includes the capacities to feel compassion for others, understand broader historical and social norms for behavior in different settings, and recognize family, school, and community resources and supports.”

Combining CASEL’s definitions provides a more holistic conception of self-awareness that requires looking both inwardly and outwardly to arrive at an elevated level of self-awareness. The organizational psychologist Tasha Eurich, who has written extensively on self-awareness and delivered a TED Talk on the subject with over four million views, takes this approach in her self-awareness definition, seeing it as an active endeavor to both look internally to see oneself clearly while also soliciting feedback from others to enrich and interrogate one’s self-perception.

Don’t Trick Yourself

So let’s now come back to Mr. Kint and the pastors of the 1800s. Concerning self-awareness, we might draw upon their sentiment to arrive at a more leadership-oriented observation: the greatest trick we’ve ever pulled is convincing ourselves we’re already sufficiently self-aware.

According to Eurich, only ~10-15% of the population is actually self-aware. She finds that as power and experience increase (dynamics that some of us conflate with expertise and accurate perception), self-awareness decreases. The more we drink our own KoolAid, the blurrier our vision becomes.

There are real consequences to diminished insights into ourselves. To borrow from another pop culture icon, you might be lacking in self-awareness if:

- You have little empathy

- You always need to be right

- You’re quick to judgment

- You crave attention

- You’re unable to accept constructive criticism

The Cost of a Lack of Self-Awareness

These are just a handful of telltale signs of a leader who lacks self-awareness and the impact on the leader and those being led. Let’s take a quick look at how just one aspect of a lack of self-awareness in leadership can be translated into the Job Demands and Resources Theory.

|

The Cost of a Lack of Self-Awareness: How Always Needing to be Right Translates into the Job Demands and Resources Theory |

|

|

Increased Demands |

Decreased Resources |

|

More effort required by those being led to stay engaged/make contributions |

Less energy available for more productive efforts |

|

Leadership stance demands an unproductive/unnecessary defense of every position/decision. |

Lower morale raises the likelihood of attrition. |

|

The extra effort required to have even a chance of getting through to the leader |

Fear/futility of challenging the leader weakens the culture. |

The table above depicts a toxic work environment that siphons adult energy from serving children more effectively. On the page, reading through the table may feel like a review of an extreme scenario. Don’t miss the opportunity to engage in a little self-awareness of your own: might any part of this scenario describe your own practice? Regardless of your answer, how do you know?

Controlling the Ups and Downs of Leadership

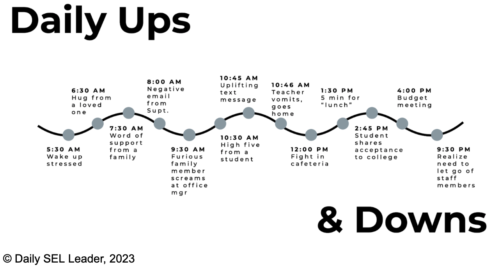

In our work, we often share the graphic below to emphasize what school leaders know all too well: there are very few if any, moments in a leader’s day that are not fraught with the intense emotion of one kind or another.

Every one of those moments is an opportunity to practice increasing self-awareness, reduce the demands we place on ourselves, and increase the resources we make available to others with whom we’re in the community. How to do it? Beat the inner devil at its own game: we can assume we’re not as self-aware as we otherwise might think we are.

A Few Ways to Operationalize Self-Awareness

- In your next meeting, actively try to agree with everything that is discussed

- When you find yourself engaged with someone else whose negative emotions are intensifying, actively accept those emotions as valid rather than try to refute or discredit them.

- Seek out the person you believe least respects or agrees with you, and invite that person to a no-agenda meeting. Just talk to each other.

The demands school leaders face and the consequences those demands can create require an unreasonable and super-human capacity to manage. Understanding how depleted leaders might fall prey to self-deception is not difficult. Increasing self-awareness can be part of the antidote, especially if we flip the script and embrace the idea that we may not be as self-aware as we think.