Table of Contents

By Betsy Hill and Roger Stark

In part one of this article, we took a look at the cognitive capacity and cognitive skills needed to build a workforce-ready employee. As we approach the mid-21st century, the need for preparing workers with the necessary skills is becoming more and more pronounced.

Neuroscience research has proven that intelligence is not fixed and that the ability to learn, think and problem-solve can be enhanced at any age. The implications of this new knowledge in the workplace are profound. It means that poorly prepared entry-level workers can make significant improvements in their ability to meet workplace requirements, becoming retrained in weeks. It means that the effectiveness of corporate training programs can be dramatically improved, whether the training is for job-specific skills or so-called soft skills like critical thinking, communication, or collaboration. It means that it is possible to develop the overall cognitive capacity of both individuals and organizations.

With that in mind, Let’s take a look at where we are currently in workforce-readiness.

Basic Reading and Math Skills

A recent study from the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy suggests that low levels of adult literacy in the workplace could be costing the U.S. a staggering $2.2 trillion per year.

And there’s more. The Department of Education says that 54 percent of U.S. adults, around 130 million people, now read below the sixth-grade level.

Other studies have identified significant gaps in the skills required for today’s jobs, estimating that between 25 percent and 40 percent of the current workforce lacks the basic skills to understand written or verbal communications.

In dollars and cents, adults’ average income at or above the minimum proficiency level for literacy is around $63,000, a number much higher than the average income of $48,000 earned by adults who are just below the minimum proficiency level. The amount is significantly higher than adults at the lower literacy levels, who earn around $34,000 per year.

When elementary and undergraduate education fails to prepare workers adequately, it falls to employers to provide remedial training. However, employers face many of the same challenges that schools and colleges face in remediating basic skills, including a broad diversity of backgrounds, attitudes towards learning, intellect and culture among their workers. However, organizations that use the same techniques and approaches used by the school systems that failed to prepare graduates for the workplace are likely to get the same result.

“The modern workplace runs very largely on the cognitive abilities of its workforce.” (Hunt and Madhyastha)

Recent research has begun to illuminate the importance of underlying cognitive skills in acquiring what many have previously considered basic reading and math skills. Researchers are showing that brain (cognitive skill) development can impact school achievement, emphasizing neurocognitive systems such as cognitive control, memory and learning. Other researchers focus on the importance of cognitive processes such as planning, attention, simultaneous and successive processing.

As a result of these and other research efforts, educational and developmental psychology researchers have started to see the need to find ways to add training of basic foundational cognitive skills to the education system to foster the acquisition of basic skills as well as higher-order processes. And in fact, such interventions have been very successful in dramatically improving cognitive skills and reading and math levels for students with learning disabilities, students from low SES, and students behind grade-level and the general population. Gains from 4 to 6 years of cognitive ability and 1 to 2 years in the level of academic performance have been shown in 12 weeks.

Job-Specific (Hard) Skills

Hard skills generally refer to the specific knowledge and abilities that are needed to perform a particular job. When it comes to the kinds of knowledge that employees need to perform their jobs effectively, this is an area where most organizations provide some kind of explicit training.

It might be training on how to cook a hamburger, how to fit pipes together in compliance with the local building code, the categories of learning disabilities that require that students receive an individualized education plan, or the cumulative knowledge needed to curate a museum collection of French Impressionist paintings. All of this knowledge (content knowledge) has to be learned, typically in an academic setting or some kind of job-related training.

While training in job-specific skills and continuing education as one’s field advances is clearly critical, many organizations have difficulty showing that training actually improves business performance. Fundamental questions haunt managers and trainers: How much do our employees remember of what we teach them? How well do they apply it on the job?

These fundamental questions beg some other questions: Do our employees understand the written, verbal and visual information they are provided during training courses? How well can they relate it to the workplace? How automatic are their responses in a workplace situation in recalling the information needed? And how effectively do they apply it in the right situations?

Training in workplace content relies on learned curriculum (reading, math, etc.), but it also assumes that workers have the underlying cognitive skills that will enable them to take in, process, absorb, retain, and recall the information the organization wants them to know. If it were possible to improve underlying cognitive skills and thereby improve understanding, memory, retrieval ability, and retention, then that would suggest that we could expect better retention of information/content contained in training programs by building stronger cognitive skills.

Results from a pilot program in 2011 suggest that inclusion of cognitive skills training on the underlying skills that correlate with workplace performance can improve overall results of an intensive new-hire training program. Two cohorts of trainees used a computer-based cognitive skills training program called BrainWare SAFARI as part of a 6-week training program to learn to be console operators in an oil refinery.

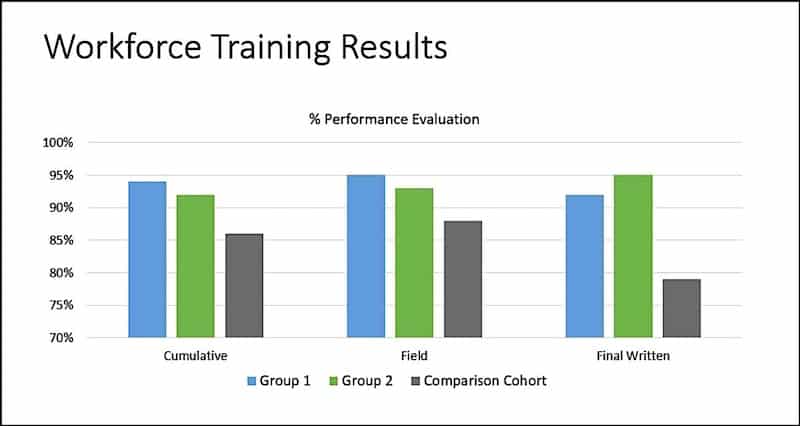

The trainees exhibited significant improvement in cognitive performance as measured by self-ratings and performance on the GAMA (General Adult Measures of Abilities), with 86 percent of the group who took the test improving their IQ score following their use of the program. Most importantly, the two groups whose training included cognitive skills training performed dramatically better on all three components of their final evaluation criteria than a previous cohort whose training did not include cognitive training, as shown in the chart below.

Consequently, all but one of the 50 members of Groups 1 and 2 met the standards to be hired by the corporation, where a drop-out/failure rate of 4 to 6 would be expected.

Soft Skills and Leadership Skills

In 2013, Google conducted a study of the skills that most predicted success at that high-tech company. Many were surprised when technological expertise was seventh on the list. It turned out that empathy, critical thinking and problem-solving, making connections across complex ideas and being a good coach were better predictors. While soft skills may be harder to measure than factual knowledge, they are arguably even more basic, perhaps even structural.

Soft skills are, in essence, how the brain works through its neural connections. These too are part of and rely on the infrastructure of cognitive capacity that employees bring to the workplace or that the workplace can help them develop there. Creativity, problem-solving, and critical thinking all rely on basic cognitive skills. It’s the ability to see patterns, see things from a different point of view, coordinate the activities of multiple areas of the brain simultaneously, and hold several ideas in the mind while thinking about them, and so forth.

Some approaches to training acknowledge the underlying cognitive processes involved in training, rehearsal and mediation. Others focus on developing familiarity with processes and techniques that are likely to leverage the brain’s metacognitive abilities to enable one to think interactively rather than make either/or trade-offs.

In 2001, Dr. Patricia Wolfe published one of the first books that explained to teachers how to apply some of the most important principles gleaned from neuroscience research to the teaching and learning process. More recently, the applicability of those findings to management and leadership has become the subject of more extensive academic work. In “Your Brain at Work” (Harvard Business Review), Waytz and Mason identify four brain networks involved in creative thinking, rewards, decision-making, cognitive control and self-regulation.

Each of these areas depends to some degree on or interacts with areas of cognitive processing that are malleable and can be developed, including foundational cognitive skills and executive functions. Just as educational practice embraces the dual benefits of strengthening both the learner’s cognitive capacity and the teacher’s effectiveness in using more brain-compatible instructional practices, the new neuroscience of leadership is beginning to show the same dual effects in a workplace setting. In this arena, one current practical application would be developing these skills in Millennials to facilitate their transition to leadership roles.

Life-Long Learning

While life-long learning applies to all workers, one top-of-mind issue is that, as baby boomers reach retirement age and birth rates in the developed world fall, employers are increasingly concerned about a shrinking workforce. Labor shortages are bringing greater competition for skilled workers, and older employees are increasingly motivated to remain in the workplace, whether to sustain their sense of self-worth or for financial reasons.

While older workers generally have many advantages, including experience, loyalty, institutional memory, and a strong work ethic, productivity can become an issue. Organizations have a compelling interest in ensuring that these workers retain the mental acuity and agility to perform optimally in their roles. Moreover, as discussed above, we can count on those roles changing. In an era of rapidly advancing technology, older workers will have to learn new things to be effective, not just in the jobs they know but in the jobs that have yet to be invented.

Indeed, the changing nature of jobs will affect all workers, not just those over a certain age. However, older workers do have some characteristics worth considering. For example, while many factors contribute to older workers’ job satisfaction, one key is ongoing professional development. Continuing to find one’s job interesting is important to older workers. According to an AARP poll, 87 percent of workers who say they plan to work in retirement will do so because of a desire to remain mentally active, and 50 percent because of a desire to learn new things.

While staying active through work may, by itself, help deter the cognitive decline associated with aging, targeted training to sustain cognitive well-being, especially in the areas of attention, memory, and processing speed, may enable older workers to be even more effective later in life. Indeed, brain fitness has the potential to become an integral part of corporate wellness programs.

Recent research documents the explosive growth in corporate wellness programs around the world, and one trend places more emphasis on technology to enable greater personalization. Indeed, just as organizations focus on preventive health programs to support physical well-being (and lower health care costs), it is expected that they will add preventative brain health to their initiatives.

Conclusion

Cognitive skills underlie the ability to learn and perform in the workplace. New tools and techniques have been developed that enable cognitive skills to be developed rapidly and dramatically. Improved cognitive skills can help organizations address key workforce issues, including:

• Re-mediating Deficiencies in Workforce Readiness

• Developing the Cognitive Capacity for Workplace

• Problem-Solving Improving the Effectiveness of Training Initiatives

• Enhancing Productivity of Older Workers

• Improving the Skills Good Leaders Need

• Improving the Learning Capacity of All Workers

Because intelligence is not fixed and the component skills that makeup intelligence and learning capacity can be trained at any age, there is reason to hope that ill-prepared entry-level workers will be able to make significant improvements in their ability to meet workplace requirements and to benefit from corporate training programs. It means that all workers can enhance their higher-order thinking and communications skills in a very short time. Older workers can be effective longer and grow in their roles.

In other words, it is possible today to train skills such as attention, visualization, working memory and auditory processing. It is possible to develop social and emotional intelligence as well as job skills and overall cognitive capacity.

If our employees are deficient in some of these skills, those deficiencies can often be remedied. If they are strong, they can become stronger. Indeed, by developing the underlying cognitive skills that allow employees’ minds to function more effectively, we should be able to develop a nation of workers at significantly more advanced levels of functioning and achievement.

What is required is that organizations begin to train the skills they need rather than bemoaning the lack of skills in those they hire. Today there is a blueprint for developing the 21st century worker, with neuroscience as the architect and with a strong and flexible mind as its foundation.

- edCircuit – Blueprint for Building a 21st Century Worker (Part 1)

- Toronto Star – We need to start giving soft skills more credit